Distal Limb Horse Lower Leg Anatomy Explained

- 1.

What is the distal limb of the horse? Let’s start at the bottom—literally

- 2.

What is proximal and distal on a horse? Anatomy’s compass, no SatNav required

- 3.

What is the distal front limb? The elegance of engineering in tweed trousers

- 4.

What are the parts of a horse limb? A roll-call fit for a royal parade

- 5.

The fetlock: not a lock, not a fet, but the hinge of glory

- 6.

Tendons & ligaments: the silent crew running the show backstage

- 7.

Blood flow down there? Oh, it’s a proper M25 at rush hour

- 8.

Common injuries—because even Olympians stub their toes

- 9.

Conformation matters—angles aren’t just for GCSE maths

- 10.

Where to go next? Keep the learning canter going

Table of Contents

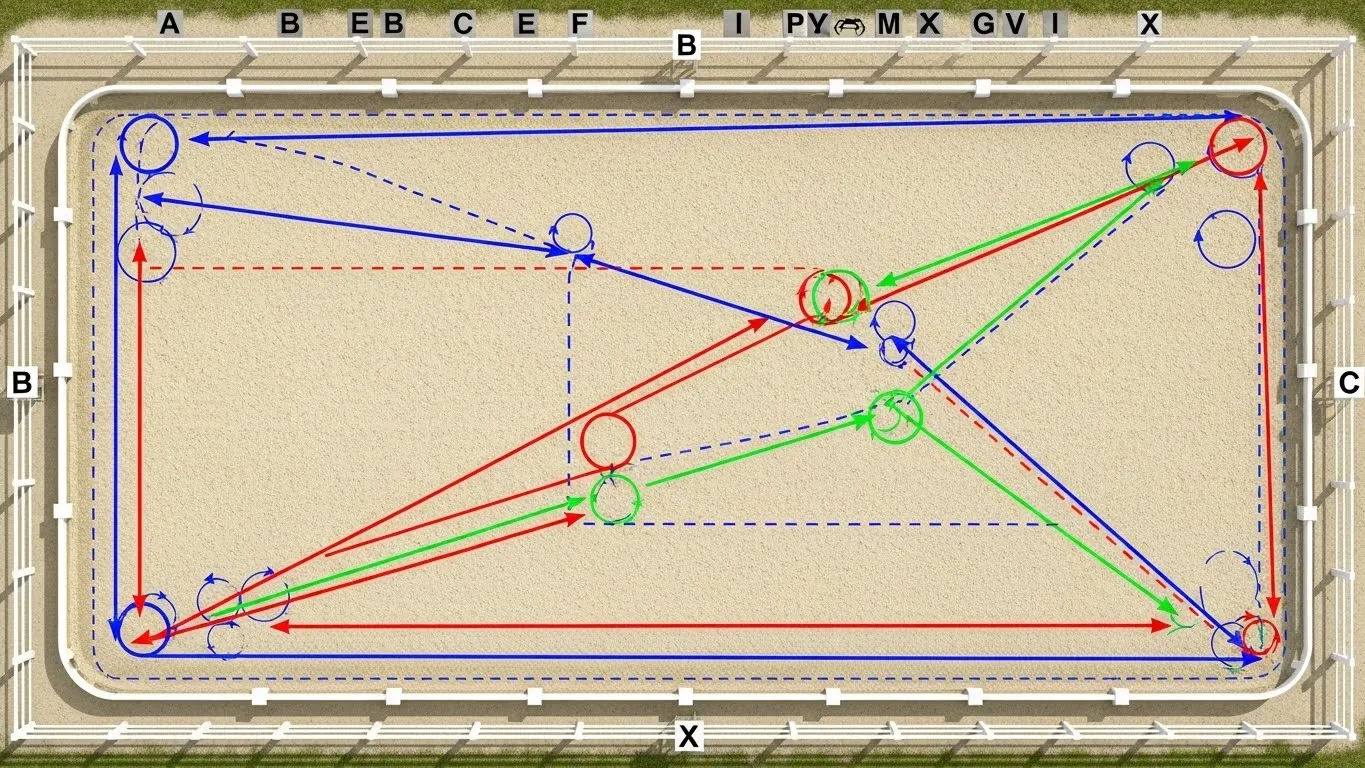

distal limb horse

What is the distal limb of the horse? Let’s start at the bottom—literally

Right then—ever looked at a horse’s leg and thought, “That’s just elegant scaffolding with a bit of fluff on top?” Bless. The distal limb of the horse is the whole business *below* the knee (front) or hock (hind)—a biomechanical masterpiece, forged by evolution, tuned by farriers, and occasionally baffled by vets. Think of it as the “business end” of equine locomotion: no muscle, *all* tendon, bone, and hydraulic finesse. From cannon bone down to hoof, it’s a tension-compression system smoother than a well-poured Guinness. In any decent distal limb horse diagram, you’ll spot three zones: *metacarpal/metatarsal* (cannon), *phalangeal* (pastern + coffin), and *hoof capsule*—each part playing its role like instruments in a chamber quartet. Miss one note? The whole symphony wobbles.

What is proximal and distal on a horse? Anatomy’s compass, no SatNav required

Righto—let’s clear the fog. In vet-speak, proximal = *closer to the body’s core* (think: shoulder, stifle), distal = *further out* (think: hoof, fetlock). So when we say “distal limb horse”, we mean *everything south of the knee/hock*. Simple? Mostly. But here’s the kicker: horses are *digitigrade*—they walk on the tip of one toe (digit III), like ballerinas on permanent pointe. That means their “hand” is buried *inside* the leg, and what looks like a knee? That’s actually their *wrist*. Confused? Grab a distal limb horse sketch—suddenly, it clicks like the latch on a well-worn tack box.

What is the distal front limb? The elegance of engineering in tweed trousers

Front legs carry ~60% of a horse’s weight, so the distal front limb is built like a suspension bridge crossed with a grandfather clock—precision under load. From top to bottom: cannon bone (metacarpal III), flanked by two *splint bones* (remnants of digits II & IV); then the *fetlock joint* (MCP)—not a true ankle, mind, more like *our* knuckle; next, the *pastern* (long + short)—a shock-absorbing duo with a 45–55° slope (steeper = speed, shallower = stamina); finally, the *coffin joint* and *hoof*. Every inch of the distal limb horse front section is tuned for elastic energy return—up to 85% of stride power comes from recoil, not muscle. Fancy that: your horse’s legs are basically *loaded springs* with a side of keratin.

What are the parts of a horse limb? A roll-call fit for a royal parade

Let’s do the full *Who’s Who* of the lower leg—no introductions needed, they’ve all got nicknames down the yard:

- Cannon bone — the “shin”, sturdy as a pub landlord’s handshake

- Fetlock — the joint that dips like a curtsy at full gallop

- Proximal phalanx (P1) — upper pastern, the diplomat of the bunch

- Middle phalanx (P2) — short pastern, the negotiator

- Distal phalanx (P3 / coffin bone) — the anchor, encased in hoof

- Navicular bone — the tiny fulcrum, often blamed unfairly

- Superficial & Deep Digital Flexor Tendons (SDFT/DDFT) — the pulley system, under constant tension

- Suspensory ligament — the safety net, fanning out like a peacock’s tail

“Know thy horse’s leg,” as the old farrier used to mutter into his tea, “or you’ll be patching up nicks well past bonfire night.” And *every* one of these bits features—bold, labelled, gloriously interconnected—in a proper distal limb horse schematic.

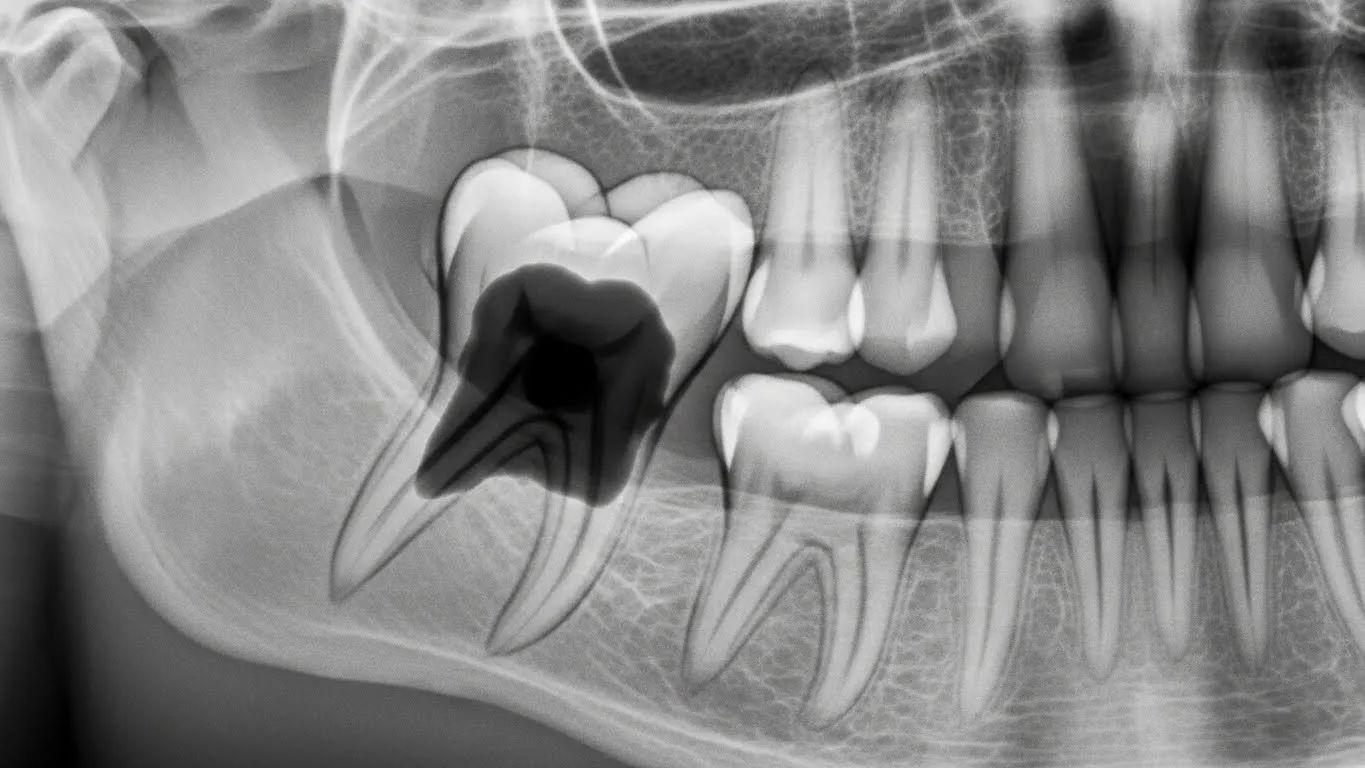

The fetlock: not a lock, not a fet, but the hinge of glory

Ah, the fetlock—misnamed, misunderstood, *massively* important. It’s not an ankle (that’s up near the hock/knee), nor is it “locking”. It’s the *metacarpo/metatarsophalangeal joint*—where P1 meets the cannon—and it’s designed to *hyperextend* under load, like a spring-loaded trapdoor. At full gallop, it drops 30–40°, storing energy in the *suspensory* and *flexor tendons*, then *boing*—releases it for propulsion. Injury here? Oof. A bowed tendon (SDFT strain) can cost £2,000+ in rehab and months off work. That’s why any distal limb horse dissection diagram lights it up like Blackpool at Christmas—central, dynamic, and non-negotiable.

Tendons & ligaments: the silent crew running the show backstage

Below the knee? Zero muscles. Just *ropes and cables* doing Herculean work. The Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon (SDFT) runs down the back, splitting at the fetlock to wrap *around* P1 like a supportive hug. The Deep Digital Flexor Tendon (DDFT)? Goes *straight through*, attaching to P3—pulling the toe down, stabilising the coffin joint. Then there’s the Suspensory Ligament—originating near the knee, branching at the fetlock into *branches* and *sesamoids*—holding everything *up*, not down. Think of them as the rigging on a tall ship: adjust one line, and the whole mast shudders. A crisp distal limb horse illustration shows these as bold, arcing lines—because without them? No canter. No jump. No walk to the haynet.

Blood flow down there? Oh, it’s a proper M25 at rush hour

How does blood get *back up* with no muscle pumps below the knee? Clever buggers, horses. Two tricks: first, the *hoof pump* (frog compression → venous squeeze); second, the *musculovenous pump*—every time the SDFT/DDFT glide, they massage the *palmar/plantar veins* nestled between them. It’s like nature’s peristalsis, but with more keratin. Disrupt it (via tight bandages, rigid shoes, or chronic box rest), and you get “stocking up”—swollen, doughy legs by evening. A top-tier distal limb horse cross-section often layers vascular maps *over* bone—red and blue rivers threading through white tendons. Poetry in physiology, that is.

Common injuries—because even Olympians stub their toes

Let’s not sugar-coat it: the distal limb horse is high-risk, high-reward. Here’s the usual suspects, ranked by frequency (BEVA, 2024 UK survey):

| Injury | Common Location | Typical Cause | Avg. Recovery (weeks) | Cost (GBP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowed tendon (SDFT) | Mid-cannon, posterior | Overextension, fatigue | 48–72 | £1,800–£4,500 |

| Suspensory desmitis | Body or branch | Concussion, conformation | 24–52 | £1,200–£3,000 |

| Navicular syndrome | Podotrochlear apparatus | Poor trim, hard ground | Chronic (manageable) | £800+/yr |

| Fetlock synovitis | Joint capsule | Repetitive strain | 6–16 | £600–£1,500 |

Moral? Respect the distal limb horse. Warm up properly, vary surfaces, trim regularly—and *watch* how they move. A slight head-bob isn’t “just a quirk”, luv. It’s a postcode for pain.

Conformation matters—angles aren’t just for GCSE maths

That *slope* from knee to hoof? Not fashion—it’s physics. Ideal front distal limb horse alignment: Shoulder: 45–50° Pastern: 45–55° (matching hoof angle) Hoof-pastern axis: straight line, no breaks Deviations? Short, upright pasterns = more concussion = DJD risk. Long, sloping pasterns = strain on flexors = tendon fatigue. Even fetlock “drop” at rest tells a tale—moderate = elastic, excessive = ligament laxity. A conformationally spot-on distal limb horse doesn’t just look balanced—it *moves* like a well-mixed cocktail: smooth, potent, and no afterburn.

Where to go next? Keep the learning canter going

Had your fill? Nah—you’ve just warmed up. For the full lowdown on equine biomechanics—from fetlock to withers—start at the hub: Riding London. Fancy structured deep-dives? Our Learn library’s got vet-reviewed guides, video dissections, and gait analysis tools. And if you’re *really* itching to geek out, don’t miss our ultra-detailed companion piece—distal limb anatomy: horse foot to knee details—with 3D layering, clinical correlations, and trimming tips from master farriers. Because knowledge? That’s the best bit of kit you’ll ever buy—and it doesn’t need re-greasing.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the distal limb of the horse?

The distal limb of the horse refers to the portion of the leg *below* the carpus (knee) in the front limb or tarsus (hock) in the hind limb. It includes the cannon bone, fetlock joint, pastern bones (P1 & P2), coffin bone (P3), navicular bone, associated tendons (SDFT, DDFT), ligaments (suspensory), and the hoof capsule. Crucially, it contains *no muscles*—movement relies on tendons and ligaments acting over distance. A labelled distal limb horse diagram is essential for visualising this complex, high-stress region.

What is proximal and distal on a horse?

In equine anatomy, proximal means *closer to the body’s centre* (e.g., shoulder, stifle), while distal means *further from the centre* (e.g., hoof, fetlock). So the *distal limb horse* region is everything distal to the knee/hock. Understanding these terms clarifies communication—e.g., a “distal check ligament” injury is near the fetlock, not the elbow. Any robust distal limb horse reference will use these directional terms consistently for precision.

What is the distal front limb?

The distal front limb specifically denotes the lower front leg—from the distal end of the radius (just above the knee) down to the ground. Key structures include the cannon (MCIII), splint bones (MCII & MCIV), fetlock joint, proximal/middle/distal phalanges (P1–P3), navicular bone, flexor tendons, suspensory apparatus, and hoof. It bears ~60% of body weight and is optimised for shock absorption and elastic energy return. A detailed distal limb horse schematic highlights how forces transmit through this column during locomotion.

What are the parts of a horse limb?

The full horse limb (front) runs: scapula → humerus → radius/ulna → carpus (knee) → cannon (MCIII) → fetlock → pastern (P1 & P2) → coffin joint & P3 → hoof. Critical soft tissues: SDFT, DDFT, suspensory ligament, check ligaments, and navicular apparatus. The distal limb horse zone excludes everything above the carpus—focusing solely on the high-impact, tendon-driven distal third. Mastery of these names—and their interplay—is non-negotiable for soundness management.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557588

- https://www.bevas.org.uk/uploads/documents/BEVA%20Guideline%20on%20Tendon%20Injury%202022.pdf

- https://www.merckvetmanual.com/musculoskeletal-system/anatomy-of-the-equine-musculoskeletal-system/limb-conformation-and-its-relationship-to-performance