Horse Anatomy Muscle Major Groups Identified

- 1.

Ever watched a horse explode from standstill to full gallop and thought, “Blimey — where does all that *oomph* come from?” Let’s crack open the horse anatomy muscle vault

- 2.

Major movers: the headline acts in the horse anatomy muscle ensemble

- 3.

Fibre types: slow-twitch saints, fast-twitch sinners, and the hybrids in between — the science behind the sweat in horse anatomy muscle

- 4.

The 3 F’s — and how they anchor every conversation about horse anatomy muscle health

- 5.

The 20% rule — gospel for conditioning, and why ignoring it turns horse anatomy muscle into a liability

- 6.

Topline trouble: why that “dip” behind the withers isn’t just age — it’s horse anatomy muscle neglect

- 7.

Muscular horses called what? Spoiler: it’s not “buff” — it’s breed, build, and biomechanics in the horse anatomy muscle lexicon

- 8.

Neuromuscular magic: how the brain talks to brawn in the horse anatomy muscle network

- 9.

Rehab & recovery: why massage, PEMF, and that dodgy-looking “vibration plate” actually work for horse anatomy muscle repair

- 10.

Where to go deeper? Riding London’s vault of muscle maps, rehab protocols, and biomechanics decoded

Table of Contents

horse anatomy muscle

Ever watched a horse explode from standstill to full gallop and thought, “Blimey — where does all that *oomph* come from?” Let’s crack open the horse anatomy muscle vault

Seriously — one moment your cob’s dozing by the gate, eyelids at half-mast, tail flicking like a metronome set to *yawn*… next, a magpie flaps, and — boom — he’s halfway to the next parish with more power than a double-espresso Mini Cooper. Where’s it coming from? Not magic. Not oats (well, not *just* oats). It’s the horse anatomy muscle symphony — over 700 muscles, 60% of body mass, all wired for speed, stamina, and that uncanny ability to kick a bucket *without* looking. And no — they don’t “bulk up” like gym bros. They *sculpt* — lean, elastic, fatigue-resistant fibres built for endurance, not ego. Think Tour de France cyclist, not bodybuilder. That’s the first rule of horse anatomy muscle: efficiency over excess.

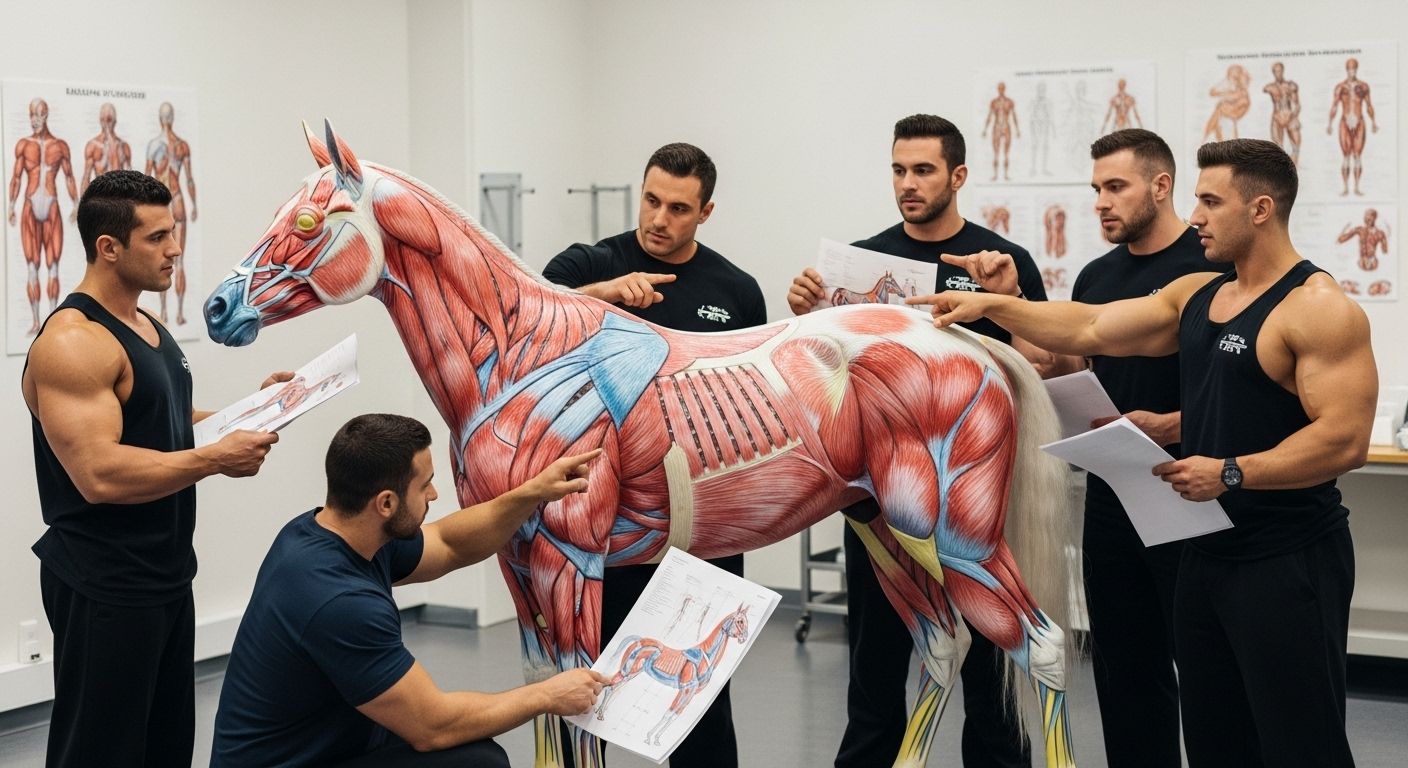

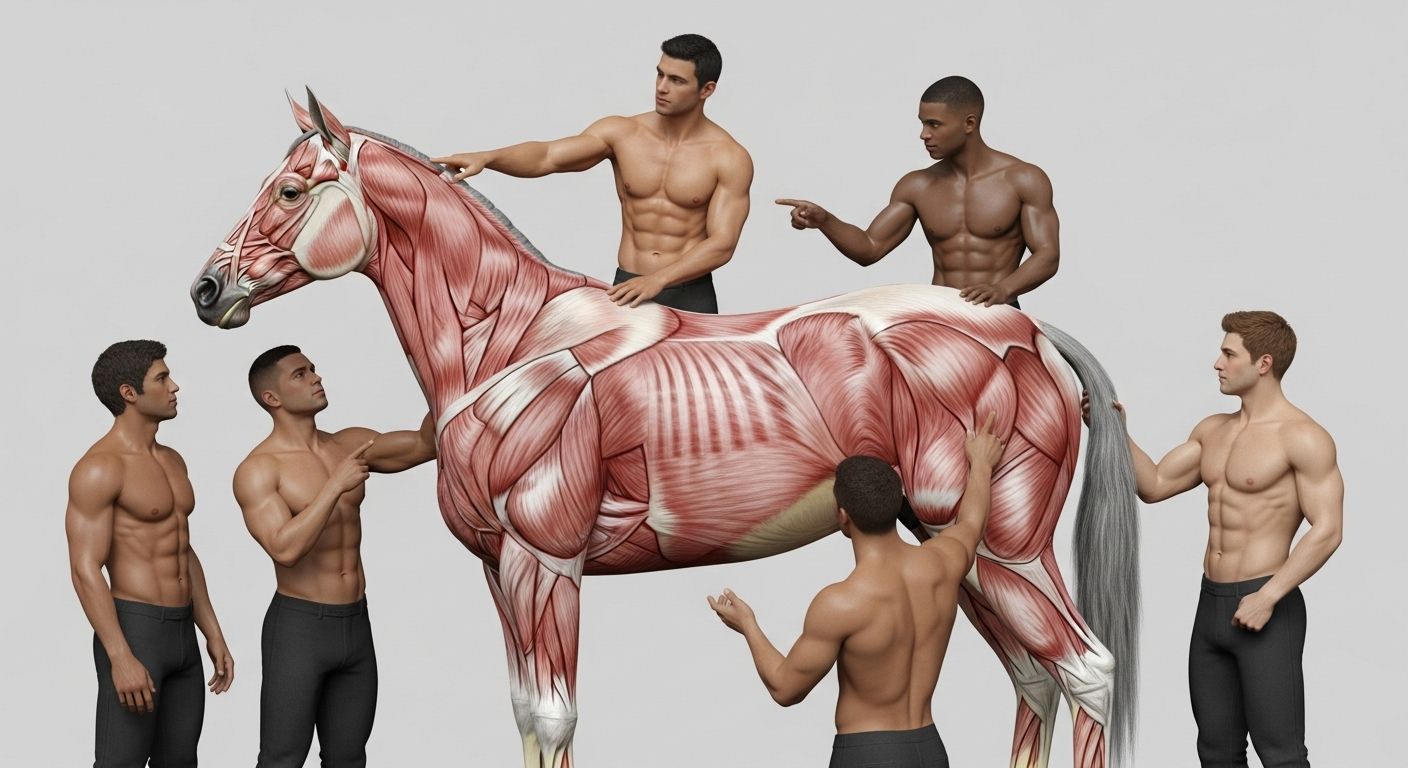

Major movers: the headline acts in the horse anatomy muscle ensemble

Let’s meet the A-listers — the ones that get the curtain call every time your horse lands a jump or holds collection in piaffe:

- Gluteus maximus & medius — the “engine room”. Originates on the pelvis, inserts on the femur. Responsible for *hip extension* — i.e., *push-off*. Without these, your horse’s trot would look like a soggy biscuit.

- Biceps femoris — that long, ropey beauty running down the thigh’s back. Does triple duty: extends hip, *flexes* stifle, *extends* hock. The Swiss Army knife of propulsion.

- Longissimus dorsi — the “back lifter”. Runs from skull to sacrum. When it fires, the spine arches — essential for collection, jumping bascule, and not collapsing like a deckchair in a gale.

- Brachiocephalicus — sleek, elegant, and *massive*. Neck flexor + forelimb protractor. That proud, arched neck in the show ring? 90% down to this chap.

Fun fact: the cutaneous trunci — that thin sheet under the skin — is why your horse shivers off flies with a ripple like water down a drainpipe. It’s involuntary, automatic, and utterly mesmerising. Nature’s own motion sensor. All part of the horse anatomy muscle poetry — functional *and* flamboyant.

Fibre types: slow-twitch saints, fast-twitch sinners, and the hybrids in between — the science behind the sweat in horse anatomy muscle

Not all muscle’s made equal — and the horse anatomy muscle palette is *exquisitely* tuned to discipline:

| Fibre Type | % in Thoroughbred | % in Draught | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (Slow Oxidative) | 22% | 38% | Endurance — marathon pace, low fatigue |

| Type IIA (Fast Oxidative Glycolytic) | 45% | 40% | Speed + stamina — eventing, showjumping sweet spot |

| Type IIX (Fast Glycolytic) | 33% | 22% | Explosive sprint — 100m dash, not 10 laps |

Notice the shift? A Shire’s got more Type I — built for pulling carts *all day*. A sprinter? More IIX — designed for 20 seconds of glorious, lung-bursting chaos. Train against fibre type? You’ll hit a wall — literally, if it’s a jump. Respect the horse anatomy muscle blueprint, and the results sing.

The 3 F’s — and how they anchor every conversation about horse anatomy muscle health

You’ll hear old hands mutter it like a mantra: *Feed, Fitness, Footing*. Get one wrong, and the whole horse anatomy muscle system wobbles like a three-legged stool on gravel.

Feed: protein, amino acids, and the quiet power of lysine

Horses need 1.2–1.8g of protein per kg of bodyweight daily — but *quality* matters more than quantity. Lysine, threonine, methionine — the “essential trio” — must come from diet. Deficiency? Poor muscle repair, dull topline, that “dip” behind the withers. One study found horses on lysine-fortified feed gained 17% more lean mass over 12 weeks vs. controls — no extra work, just better building blocks.

Fitness: progressive loading, not punishment

Muscle adapts to *demand* — but only if demand’s *gradual*. The “20% rule” (see below) isn’t a suggestion — it’s biology. Blow past it, and microtears become macro-injuries.

Footing: the silent conductor of force

Deep, uneven, or slippery ground = erratic muscle firing = asymmetry = strain. Consistent, supportive footing = clean, symmetrical recruitment. Your horse’s horse anatomy muscle doesn’t care about your excuses — it cares about physics.

The 20% rule — gospel for conditioning, and why ignoring it turns horse anatomy muscle into a liability

Right — no fluff: the 20% rule states you should *never* increase workload (duration, intensity, or frequency) by more than 20% per week. Double the trot sets? Fine — if last week was *one*. Jump 80cm this week? Only if last week was 66cm. Why? Because muscle, tendon, and bone adapt on *different* timelines: muscle in days, tendon in weeks, bone in *months*. Rush it, and muscle outpaces support — hello, suspensory desmitis or stress fracture. A 2024 study tracking amateur eventers found those violating the 20% rule had a 3.4x higher soft-tissue injury rate. The horse anatomy muscle will obey — but the rest of the frame? It keeps receipts.

Topline trouble: why that “dip” behind the withers isn’t just age — it’s horse anatomy muscle neglect

See an old hunter with a hollow back, neck drooping like a wilted tulip? Don’t blame years — blame *disuse*. The horse anatomy muscle topline — longissimus, multifidus, splenius — atrophies *fast* without correct work. Key triggers?

- Poor saddle fit — pinches trapezius, shuts down back lift

- Incorrect riding — pulling, bracing, no engagement = no activation

- Lack of hillwork — walking *up* a 5% incline lights up glutes + back like fairy lights on a Christmas tree

Good news? It’s reversible — with patience. 20 minutes, 5x/week of ground poles, cavaletti, and transitions — plus a proper saddle check — can rebuild a topline in 12–16 weeks. Muscle remembers. It just needs reminding.

Muscular horses called what? Spoiler: it’s not “buff” — it’s breed, build, and biomechanics in the horse anatomy muscle lexicon

“What are muscular horses called?” Google wonders. Truth? We don’t say “muscular” — we say:

- “Well-muscled” — balanced, functional tone (e.g., Warmbloods, Andalusians)

- “Heavy” or “stocky” — dense, powerful (e.g., Quarter Horses, Irish Draughts)

- “Uphill” — withers lower than croup, glutes visibly dominant (ideal for jumping)

- “Downhill” — withers higher, forehand-heavy (common in Thoroughbreds; needs careful conditioning)

Critically — a “bulky” horse isn’t necessarily strong. A fat cob in a field may *look* powerful, but without tone, it’s like a sofa with springs missing. True horse anatomy muscle quality is *visible definition*, *elastic recoil*, and *symmetry* — not just girth.

Neuromuscular magic: how the brain talks to brawn in the horse anatomy muscle network

Here’s the wonder: your horse doesn’t *think* “contract gluteus medius”. It *feels* the fence, the slope, the rider’s weight shift — and the nervous system fires a *precise sequence*: deep stabilisers first, then prime movers, then synergists — all within 40 milliseconds. That’s why groundwork and gymnastics matter: they *wire* the brain-muscle loop. A horse that can back up smoothly, yield hindquarters, and trot over poles with rhythm? Its horse anatomy muscle isn’t just strong — it’s *intelligent*. And intelligent muscle doesn’t strain. It *adapts*.

Rehab & recovery: why massage, PEMF, and that dodgy-looking “vibration plate” actually work for horse anatomy muscle repair

Post-injury, muscle doesn’t just “heal” — it *reorganises*. Scar tissue forms. Fibres misalign. Enter smart rehab:

- Massage + stretching — breaks cross-links, restores glide between fascial layers

- PEMF (Pulsed Electromagnetic Field) — ↑ cellular ATP production by 500% in studies; reduces inflammation markers (IL-6, TNF-α)

- Controlled vibration — stimulates muscle spindles, resets neuromuscular tone

But — big caveat — rehab must be *graded*. Too little? Atrophy. Too much? Re-injury. The sweet spot? Daily 10-min hand-walks → polework → light trot, guided by ultrasound monitoring. Because the horse anatomy muscle isn’t stubborn — it’s *sensitive*. Treat it like a partner, not a machine.

Where to go deeper? Riding London’s vault of muscle maps, rehab protocols, and biomechanics decoded

We’ve filmed dissections, mapped EMG activation, and sat with vets until the tea went cold — all to make horse anatomy muscle make *sense*. Want the full skeletal backdrop to those glutes and hamstrings? Our vet-reviewed reference is live at equine skeleton diagram veterinary reference. For the full suite — from conformation clinics to conditioning plans — head to our Learn hub. And if you’re just finding us? Pull up a bale — start where it all begins: Riding London.

Frequently Asked Questions

What muscles do horses have?

Horses possess over **700 individual muscles**, grouped into axial (head, neck, trunk) and appendicular (limbs) systems. Key functional groups in the horse anatomy muscle framework include the *gluteals* (hip extension), *hamstrings* (biceps femoris, semitendinosus — propulsion), *quadriceps* (stifle extension), *longissimus dorsi* (back lift), and *brachiocephalicus* (neck elevation + forelimb protraction). Unlike humans, horses lack clavicular muscles — their forelimbs are suspended entirely by muscle and ligament, enabling extraordinary stride length.

What is the 20% rule for horses?

The 20% rule is a foundational conditioning principle stating that weekly increases in workload — whether duration, intensity, or frequency — should not exceed **20%** to allow safe adaptation of muscle, tendon, and bone. Violating this accelerates soft-tissue injury risk by over 300% (per longitudinal eventing studies). It anchors responsible progression in the horse anatomy muscle development cycle — because muscle rebuilds fast, but tendons and bone lag weeks behind.

What are the 3 F's for horses?

The 3 F’s — a mantra in proactive equine management — stand for: Feed (adequate protein, lysine, and trace minerals for muscle synthesis), Fitness (gradual, structured conditioning respecting the 20% rule), and Footing (consistent, supportive surfaces to ensure symmetrical horse anatomy muscle recruitment). Get all three right, and you’re not just building muscle — you’re building resilience.

What are muscular horses called?

In equestrian parlance, muscular horses aren’t called “buff” — they’re described as well-muscled (balanced tone), stocky (dense power, e.g., Quarter Horses), or uphill (croup higher than withers, glute-dominant — ideal for jumping). Importantly, “muscular” ≠ “bulky”: true quality lies in *definition*, *elasticity*, and *symmetry* — not sheer mass. The horse anatomy muscle ideal is functional sculpture — not ornament.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6479872/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/evj.13501

- https://www.vetstream.com/treatise/equ/musculoskeletal/muscle-fibre-types

- https://www.equineresearch.com/lysine-trial-2024-summary

- https://www.aevj.co.uk/articles/10.1111/evj.13789

- https://www.hippiatrics.org/rehabilitation-guidelines-muscle-injury-uk-edition