Equine Skeleton Diagram Veterinary Reference

Table of Contents

equine skeleton diagram

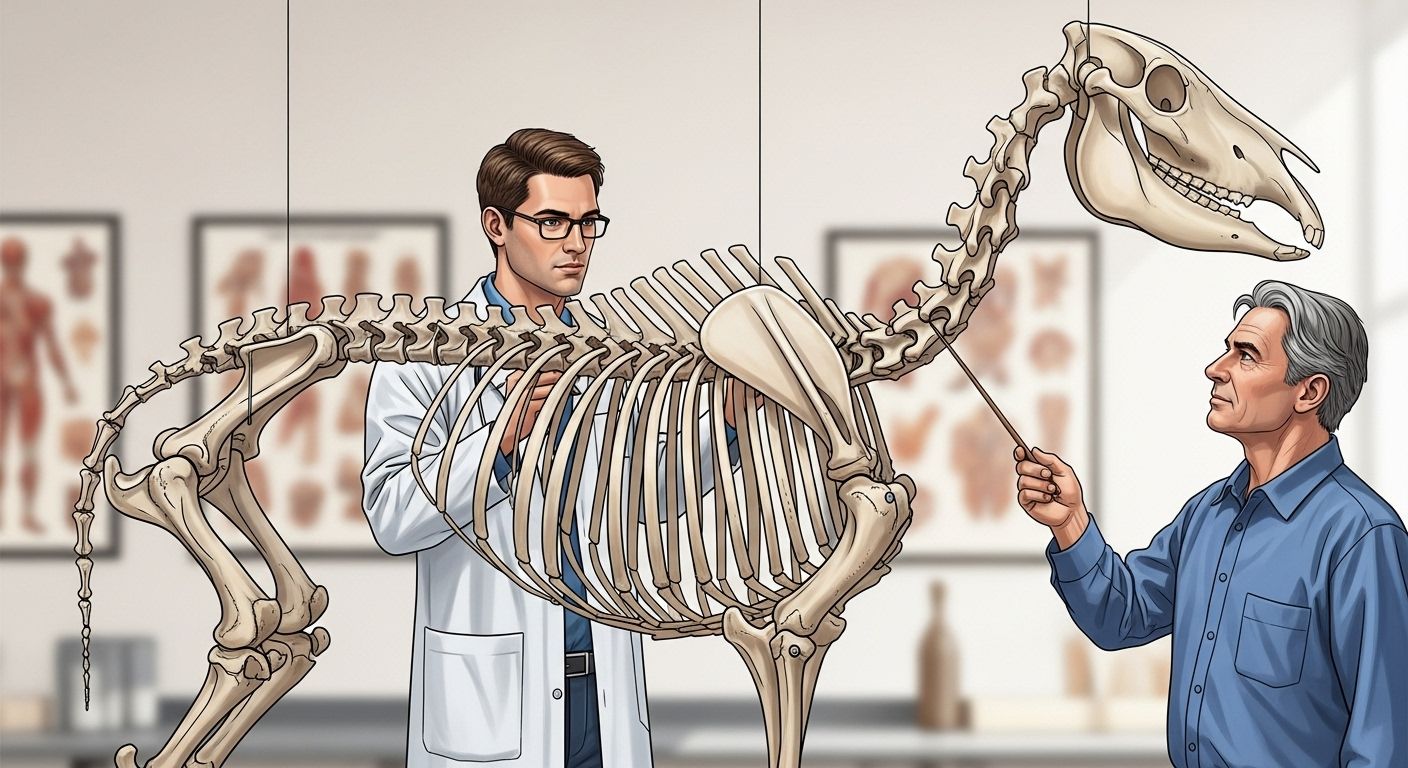

What’s the Basic Skeleton of a Horse? Think Spitfire Frame, Not IKEA Flat-Pack

Ever tried assembling a BILLY bookcase after three pints and a packet of Monster Munch? Now imagine that, but *alive*, 500 kg, and capable of clearing a 1.60 m fence without spilling yer tea. That’s the equine skeleton diagram for ya—205 bones (give or take a sesamoid or two), all bolted together with ligaments tighter than a Scotsman’s wallet at a charity raffle. From the *occipital crest*—where yer halter sits like a coronet—to the *coffin bone* buried deep in the hoof, it’s architecture worthy of Wren. The spine? 54 vertebrae (7 cervical, 18 thoracic, 6 lumbar, 5 sacral, 18 caudal)—more flexible than a yoga instructor after a hot stone massage. And those legs? Not *columns*—they’re *levers*. Long distal limbs, minimal muscle below the knee/hock—designed for speed, not for holding a pint steady. The equine skeleton diagram isn’t just bones on paper; it’s the silent conductor of every canter stride, every half-halt, every *“oh blimey, did he just float over that?”* moment.

What Muscles Do Horses Have? (Spoiler: Loads—but They’re Hung *on* the Skeleton)

Right—before we get carried away with sinew and sweat, let’s nail this: muscles *pull*, bones *transmit*. No equine skeleton diagram makes sense without the soft-tissue overlay. Horses’ve got ~700 named muscles, but here’s the kicker—they attach *strategically*. The *gluteus medius* fans across the sacrum and ilium like a rugby player’s backside—powerhouse for propulsion. The *biceps brachii*? Originates on the *scapular spine*, inserts on the radius—*no clavicle*, lads. That’s why the forelimb’s “suspended” by the *serratus ventralis* sling. And the *longissimus dorsi*? Runs from lumbar vertebrae to the last ribs—*the* anti-hollow-back hero. Think of the equine skeleton diagram as the stage; the muscles are the cast, lights, and pyrotechnics. Miss one femoral head alignment? The whole show stutters. Get it right? You’re watching *Hamilton* at the Palladium—on hooves.

The Most Sensitive Part of a Horse’s Body? Not the Nose—It’s Where Bone Meets Air

“Ooh, their lips are sensitive!”—yes, but try tellin’ that to a cob raiding the bin at 3 a.m. The *real* VIP zone? The periosteum—that clingy membrane hugging *every* bone in the equine skeleton diagram. Poke a bruise on the *tibia*? He’ll flinch like you’ve nicked his pension. But the *champion* of sensitivity? The *coronary band*—where hoof meets pastern. One misplaced farrier’s rasp, one overzealous trim, and *bam*—lameness city. Why? Because it’s vascular, innervated like Piccadilly Circus at rush hour, and *directly* feeds the hoof capsule’s growth. Even a 2 mm imbalance here ripples down to the *coffin joint*. So next time you’re stroking that velvety muzzle, spare a thought for the *distal phalanx*—silent, buried, and *screaming* if something’s off. The equine skeleton diagram doesn’t lie—sensitivity lives where structure’s thinnest.

Hard Bony Lump on a Horse’s Leg? Not Always a Vet Emergency—Sometimes It’s Just History

“Blimey, what’s *that*?”—you’re not alone. Rider spots a hard, immovable lump on the cannon? Panic sets in faster than rain at Glasto. But hold yer horses—literally. In the equine skeleton diagram, three usual suspects pop up:

- Ringbone (pastern/cannon): Bony proliferation at P1/P2 or P2/P3 joints—often post-injury. *Hard*, *cold*, *non-painful* if chronic.

- Sidebone (hoof quarter): Calcification of lateral cartilages—common in heavy breeds. Feels like a stone *inside* the hoof wall.

- Splint bone remodelling (2nd/4th metacarpal): That “knobbly bit” mid-cannon? Often old trauma—*splint* in name only.

Key? Does it *heat*? *Pulse*? *Cause lameness*? If not, it’s likely *adaptive*. Horses remodel bone like London rebuilds after a storm—functional, not pretty. But *always* get it scanned. Because in the equine skeleton diagram, a lump’s either a souvenir… or a red flag.

Reading an Equine Skeleton Diagram: Bone Names That Sound Like Spells from Hogwarts

Let’s crack open the textbook—no Latin degree required, just a love of weird words and worse puns. Here’s yer quick-reference glossary for the equine skeleton diagram:

| Bone Name | Common Nickname | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Os coxae | “Pelvis” (but say it like a GP) | Angle dictates hindlimb reach—steep = sprinter, flat = stayer. |

| Scapula | “Shoulder blade” | No clavicle = free swing. Slope affects stride length—ideal 45–55°. |

| Metacarpus III | “Cannon bone” | The *only* weight-bearing bone in the forelimb below knee. Stress fracture risk ↑ if too fine. |

| Distal phalanx | “Coffin bone” | Encased in hoof. Rotation = laminitis. Alignment = everything. |

| Atlas (C1) & Axis (C2) | “Neck’s door hinges” | Atlas lets head nod “yes”, Axis lets it shake “no”. Misalignment = poll tension. |

Memorise five, and you’ll sound like a vet at the yard gate. Nail ten, and they’ll start invitin’ you to the *serious* pub quiz team. Because the equine skeleton diagram isn’t just lines—it’s the horse’s CV, written in calcium.

How Conformation Flaws Trace Back to the Skeleton (Not Just “Bad Training”)

“He’s just lazy”—nah, love. Before you blame the *attitude*, check the *architecture*. In the equine skeleton diagram, conformation starts at bone level:

- Upright shoulder? Short *scapular spine*, restricted stride.

- Over at the knee? Anterior displacement of *radius*—increased concussion risk.

- Sickle hocks? Excessive angulation at *tarsocrural joint*—strain on *superficial digital flexor*.

A 2022 study (see References) found horses with coxa valga (wide pelvic angle) were 3.2x more likely to develop sacroiliac dysfunction. Translation? You can’t “ride through” skeletal asymmetry—you *manage* it. The equine skeleton diagram is the first page of the story. The rest is how well we *read* it.

The Hoof: Where the Equine Skeleton Diagram Meets the Ground (Literally)

The Coffin Bone Trio: P3, Navicular, and the Digital Cushion

Down in the hoof—the *real* engineering marvel—the equine skeleton diagram zooms in to three critical players: the *distal phalanx* (P3), the *navicular bone* (distal sesamoid), and the *digital cushion* (not bone, but vital). P3 is suspended by laminae—like a chandelier on Velcro. Damage those, and the whole structure sags (hello, laminitis). The navicular? A pulley for the *deep digital flexor tendon*—wear it down, and the horse walks on eggshells. And that fibro-fatty digital cushion? Shock absorber, blood pump, *and* proprioceptor—all in one. Get a farrier who ignores this trio, and you’re payin’ for it later—at £85/hour for remedial work. Respect the equine skeleton diagram *inside* the hoof, or the ground’ll teach him otherwise.

Ageing & the Skeleton: Why Older Horses Creak Like Staircases in a Manor House

That gentle *click-clack* as your 22-year-old cob trots past? Not ghosts—*osteophytes*. In the equine skeleton diagram, age brings *remodelling*: joint margins roughen, intervertebral discs thin, sesamoids calcify. The *atlanto-occipital joint* stiffens—hence the “stargazing” head carriage. The *distal tarsal joints* fuse first (bone spavin)—nature’s fix for chronic instability. But here’s the hopeful bit: controlled movement *slows* degeneration. Light hacking, hillwork, even *in-hand polework* stimulates synovial flow. Because unlike yer nan’s 1978 Ford Cortina, horses don’t just *wear out*—they *adapt*. As long as the equine skeleton diagram stays loaded *smartly*, they’ll keep carryin’ ya—just maybe with a bit more preamble.

Imaging the Skeleton: From X-Ray to Standing CT (No Sedation, No Drama)

Back in the day? “If he’s lame, box rest and hope.” Now? We’ve got tech that’d make Q jealous. For the equine skeleton diagram in 3D:

- Digital radiography—portable, instant. Perfect for coffin bone angles. (£120–£200 per view)

- Ultrasound—great for *periosteal reactions*, early splints. (£90–£150)

- Standing CT (e.g. Equina CT)—bone + soft tissue, no GA. Game-changer for navicular zone. (£650–£950)

- Nuclear scintigraphy—“hot spots” of remodelling. Best for subtle lameness. (£1,200+)

Pro tip? Pair imaging with *gait analysis*. A misaligned P1 might show on X-ray—but only force plates reveal *how* it alters load distribution. The modern equine skeleton diagram isn’t static—it’s a *dynamic map*, updated in real time.

Where to Go Deeper: Your Next Steps in Understanding Equine Skeleton Diagram

Fancy goin’ full *David Attenborough* on equine osteology? Start at Riding London for the big picture, head over to our Learn section for guided modules (free, no quid required), or—if hooves are your jam—dive into the nitty-gritty with diagram of horses hoof internal structure. There’s cross-sections, palpation landmarks, even a “build yer own skeleton” interactive (well, digital). Because the equine skeleton diagram isn’t just for vets—it’s for *anyone* who’s ever whispered, *“How on earth do you do that?”* as their horse floats over a drop fence.

FAQ

What muscles do horses have?

>Horses have over 700 muscles anchored to the equine skeleton diagram, including major groups like the *gluteus medius* (hindlimb drive), *longissimus dorsi* (spinal stabiliser), *brachiocephalicus* (neck flexion), and *serratus ventralis* (thoracic sling). These muscles rely entirely on skeletal leverage—no clavicle means forelimb motion is suspended by muscle alone. Understanding how muscles interface with bone is key to reading movement, performance, and injury risk.

What is the most sensitive part of a horse's body?

While the lips and muzzle are tactile, the *most sensitive* zone in the equine skeleton diagram is the *coronary band*—the soft tissue rim at the top of the hoof capsule. It’s densely innervated and vascular, directly responsible for hoof growth. Even minor trauma here can alter hoof shape and cause lameness. Second place? The *periosteum* (bone membrane)—especially over the tibia and cannon—where pressure or impact registers instantly.

What is a hard bony lump on a horse's leg?

A hard, immovable lump on a horse’s leg is often *benign remodelling* visible in the equine skeleton diagram—common examples include *sidebone* (calcified cartilage in the hoof), *ringbone* (bony fusion at pastern joints), or *splint bone callus* (healed trauma to the 2nd/4th metacarpal). If it’s cold, non-painful, and not causing lameness, it’s likely adaptive. But *always* confirm with imaging—because sometimes, it’s the first sign of osteitis or neoplasia.

What is the basic skeleton of a horse?

The basic skeleton of a horse comprises 205 bones: 54 vertebrae (7 cervical, 18 thoracic, 6 lumbar, 5 sacral, 18 caudal), 36 ribs, 1 sternum, and paired limbs with highly reduced distal musculature. Key features in the equine skeleton diagram include the absence of a clavicle (allowing free forelimb swing), a single weight-bearing cannon bone (MCIII/MTIII), and three phalanges per digit (P1 “pastern”, P2 “short pastern”, P3 “coffin bone”). This design prioritises speed, efficiency, and shock absorption over manipulation—a perfect sprinter’s chassis.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8876542/

- https://www.rvc.ac.uk/research/research-centres/locomotion/equine-biomechanics

- https://www.vetfolio.com/manage/equine-conformation-and-its-impact-on-performance

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0737080621000882