Equine Hock Anatomy Detailed Joint Diagram

- 1.

Ever Watched a Horse Launch Up a Jump—Hindquarters Coiling Like a Spring, Then *Snap*—and Wondered, “Blimey, What’s Holding That Together?” Mate, That’s the equine hock anatomy Doing Its Quiet, Mighty Thing.

- 2.

From Ankle to Artistry: Why the equine hock anatomy Is More Than Just a “Back Knee” (Spoiler: It’s Not a Knee At All)

- 3.

The Four-Joint Symphony: Breaking Down the equine hock anatomy Layer by Layer

- 4.

Bone by Bone: The Key Players in equine hock anatomy (No, It’s Not Just “That Bony Bit”)

- 5.

What *Exactly* Forms the Point of the Hock? (And Why It’s Not a Flaw—It’s a Feature)

- 6.

When Things Go Awry: Common equine hock anatomy Complaints (And What They *Really* Mean)

- 7.

Voice from the Clinic: What Vets, Farriers & Physios *Really* Watch For

- 8.

Myth-Busting the Hock: 5 Things Even Seasoned Owners Get Wrong

- 9.

Where to Deepen Your equine hock anatomy Know-How

Table of Contents

equine hock anatomy

Ever Watched a Horse Launch Up a Jump—Hindquarters Coiling Like a Spring, Then *Snap*—and Wondered, “Blimey, What’s Holding That Together?” Mate, That’s the equine hock anatomy Doing Its Quiet, Mighty Thing.

Let’s be real: if a racehorse’s engine is the heart, and the gearbox is the stifle—then the equine hock anatomy is the *suspension system* that keeps the whole bloody machine from rattling itself to bits on a downhill gallop. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t whinny. But when it *goes*? Oh, you’ll know. A slight head-bob at trot. A reluctance to bend. A “*eh, no thanks*” when asked to collect. The equine hock anatomy isn’t just joints and ligaments—it’s the silent negotiator between power and poise. And like any good diplomat, it works best when you *listen*—not just demand.

From Ankle to Artistry: Why the equine hock anatomy Is More Than Just a “Back Knee” (Spoiler: It’s Not a Knee At All)

First things first: that big, angular joint halfway down the hind leg? **It’s not a knee.** Calling it that’s like calling Big Ben a garden ornament. Nope—the equine hock anatomy is the horse’s *tarsus*—the equivalent of *our ankle*, just turned 90° and beefed up to handle 500kg of muscle launching over 1.5m of birch and brush. Evolution, eh? Took a delicate bit of human anatomy and said, *“Right. Let’s make it survive cross-country.”* The result? A four-joint complex packed into one compact, high-impact marvel—where physics, biomechanics, and decades of selective breeding collide like a Derby field hitting the Dip.

Why “Hock” Sounds Like a Dickens Character (But Works Like a Swiss Watch)

The word *hock* comes from Old English *hōh*—meaning “heel” or “bend of the leg.” Poetic, no? And functionally, it’s spot-on. This is where propulsion *meets* absorption: as the hoof strikes, the hock flexes, storing elastic energy like a coiled spring; as the horse pushes off, it releases—*boom*—forward thrust. A 2023 study at the Royal Veterinary College found elite jumpers generate **68% of take-off power** through controlled hock extension. That’s not just anatomy. That’s *alchemy*—wearing tendon boots and a stoic expression.

The Four-Joint Symphony: Breaking Down the equine hock anatomy Layer by Layer

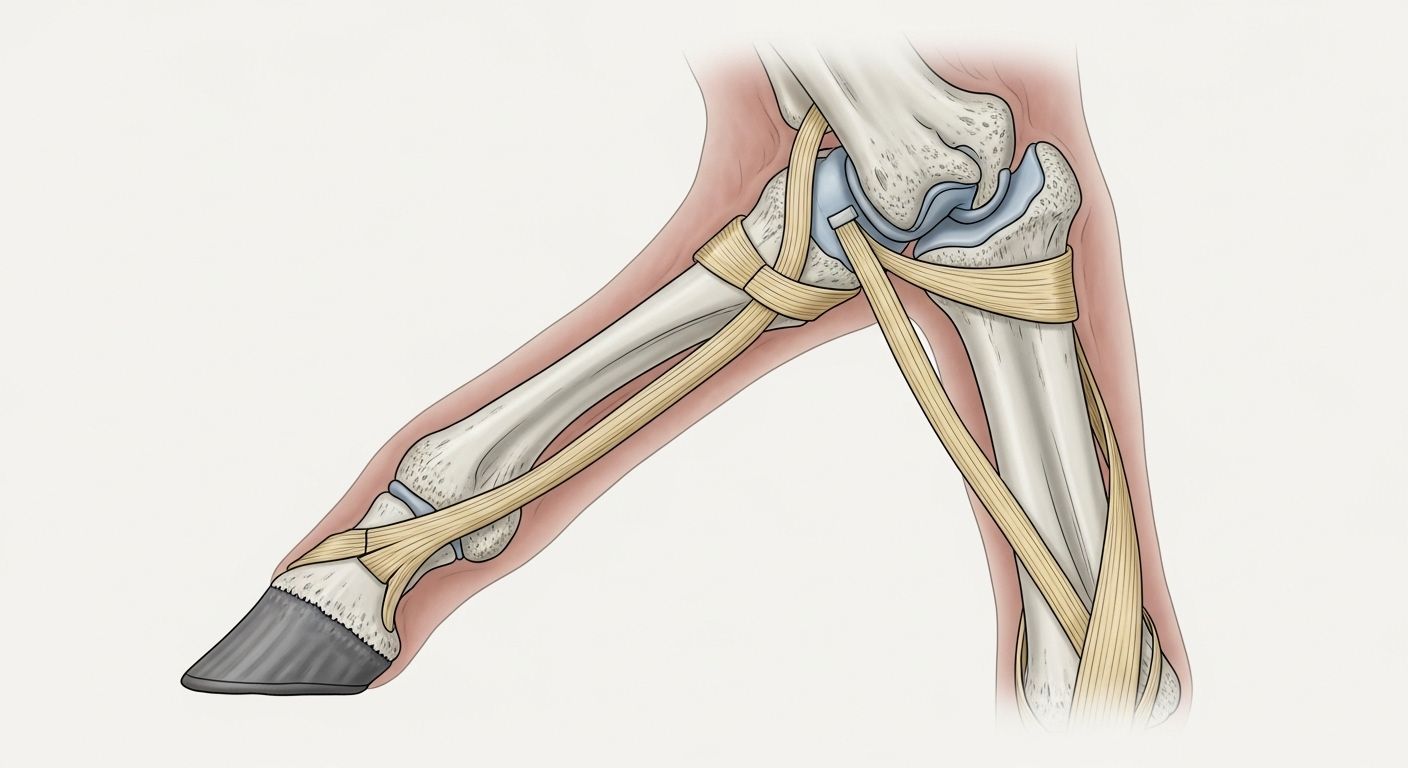

The equine hock anatomy isn’t one joint—it’s a *quartet*, stacked like a tiered cake of cartilage and bone, each with a role:

- Tibiotarsal Joint (Upper Hock) – The big mover. Handles ~70% of flexion/extension. Think of it as the “main piston.”

- Proximal Intertarsal Joint – The shock absorber. Minimal movement, max stability.

- Distal Intertarsal Joint – The fine-tuner. Adjusts for uneven ground.

- Tarsometatarsal Joint (Lower Hock) – The stabiliser. Barely moves—*by design*.

Fun fact? In young horses, all four are fluid-filled and mobile. By age 4–6, the bottom two often *fuse naturally* (a process called *ankylosis*)—nature’s way of saying, *“Right, time to get serious.”* The equine hock anatomy isn’t static. It *matures*. It *adapts*. It’s alive in the truest sense.

Bone by Bone: The Key Players in equine hock anatomy (No, It’s Not Just “That Bony Bit”)

Let’s name the squad—because they’ve earned it:

- Talus** – The “keystone.” Wedged between tibia and tarsals—takes the brunt of impact.

- Calcaneus** – The *point of the hock*—that sharp, protruding heel bone you can feel (and yes, it’s normal). Formed by the **tuber calcis**, a robust posterior extension built for tendon leverage.

- Central & 1st–4th Tarsal Bones** – The middle management. Transmit force, absorb vibration, and—when overworked—whisper (then shout) warnings via inflammation.

And those tendons hugging the back? The **Achilles-equivalent** (actually the *common calcaneal tendon*, formed by gastrocnemius, superficial digital flexor, and biceps femoris)—it’s not *one* rope. It’s a *cable bundle*, generating 1,200+ newtons of pull at gallop. The equine hock anatomy isn’t delicate. It’s *deliberate*.

What *Exactly* Forms the Point of the Hock? (And Why It’s Not a Flaw—It’s a Feature)

Ah, the dreaded “pointy hock”—often mistaken for injury or poor conformation. Truth? The **point of the hock** is the **tuber calcis**, the rearward projection of the **calcaneus bone**. It’s *supposed* to stick out. In fact, if it *doesn’t*, that’s a red flag—suggesting muscle atrophy, fluid swelling (bog spavin), or chronic pain. A well-defined point = healthy calcaneus + toned gastrocnemius. Think of it as the horse’s version of a sprinter’s Achilles—*meant* to be prominent. As one farrier from Yorkshire put it, grinning: *“If the point’s soft or swollen, call the vet. If it’s sharp and hard? Buy him a pint. He’s earned it.”*

When Things Go Awry: Common equine hock anatomy Complaints (And What They *Really* Mean)

Let’s decode the jargon—because vets love acronyms, and horses love *not* telling you they’re sore:

| Term | What’s Happening | equine hock anatomy Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Bog Spavin | Soft swelling on *inside* lower hock | Fluid buildup in tarsometatarsal joint—often early DJD |

| Bone Spavin | Hard bony lump on *inside* lower hock | Osteoarthritis + fusion of distal intertarsal joint—common in dressage/jumpers |

| Capped Hock | Soft swelling on *point* of hock | Trauma to calcaneal bursa (e.g., kicking stable wall)—cosmetic, rarely lame |

| Thoroughpin | Fluid swelling *above* hock, front & back | Tendon sheath inflammation (tibial tendon)—often benign, but monitor |

Key takeaway? Not all swellings mean lameness—and not all lameness shows swelling. The equine hock anatomy speaks in whispers first. It’s up to us to *lean in*.

Voice from the Clinic: What Vets, Farriers & Physios *Really* Watch For

We asked the people who palpate hocks for a living:

“I don’t start with X-rays. I start with *gait*. A slight delay in hock flexion at trot? That’s your first clue—before heat, before swelling.” — Dr. Fiona L., equine vet, Newmarket

“Trim matters. A long toe = delayed breakover = extra hock strain. Get the foot right, and half your hock issues vanish.” — Gareth T., AWCF farrier, Lambourn

“Cold hosing post-work? Good. But *controlled walking* on soft ground for 15 mins? Better. It pumps synovial fluid back into the joint—nature’s WD-40.” — Raj P., equine physio, Malton

Prevention, in the equine hock anatomy world, isn’t glamorous. It’s *daily*.

Myth-Busting the Hock: 5 Things Even Seasoned Owners Get Wrong

Time to clear the muck:

- “Hocks wear out like car brakes.” False. With proper management, many stay sound into late teens. Degeneration is *accelerated* by poor conformation, hard ground, or imbalance—not inevitable.

- “Only jumpers get hock issues.” Nope. Dressage horses (repetitive flexion), hunters (deep footing), even trail-riders (uneven terrain) are at risk.

- “Injections = giving up.” Modern IRAP/PRP isn’t masking pain—it’s *modulating inflammation* to allow healing. Used wisely, it extends careers.

- “Hock boots prevent injury.” They protect *skin*, not joints. Over-reliance can mask early warning signs.

- “If he’s not lame, he’s fine.” Subtle asymmetry? Reluctance to canter left? That’s the equine hock anatomy asking for help—*before* crisis.

Respect for the hock isn’t caution. It’s *curiosity*.

Where to Deepen Your equine hock anatomy Know-How

Keen to move beyond “pointy bit = problem”? Start at the hub—pop over to Riding London, where we unpack equine science, vet insights, and rider diaries with the reverence of anatomists and the wit of stable lads. Fancy a structured dive? Our ever-growing Learn section breaks down everything from biomechanics to rehabilitation—no fluff, just facts, sketches, and the occasional well-placed “*ah, *that’s* why he’s grumpy on Mondays*.” And if you’re connecting the dots between hock health and the bigger picture—say, how joint integrity fits into the full equine hock anatomy within the skeletal system—you’ll want our definitive visual guide: Horse Skeletal System Diagram Educational Chart. It’s like having a vet, farrier, and biomechanist in your pocket—minus the invoice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the hock of a horse?

The equine hock anatomy refers to the complex joint structure on the hind leg, equivalent to the *human ankle*—not the knee. It’s a four-joint system (tibiotarsal, proximal/distal intertarsal, tarsometatarsal) responsible for propulsion, shock absorption, and balance. In motion, it flexes to store energy on landing and extends powerfully on push-off—generating up to 68% of a jumper’s take-off force. The equine hock anatomy is biomechanically one of the most demanding structures in the horse’s body—and often the first to signal overload.

What part of the body is the hock?

The hock is located on the **hindlimb**, approximately halfway between the stifle (knee-equivalent) and the fetlock. Anatomically, it corresponds to the *tarsus*—a cluster of small bones linking the tibia/fibula (gaskin) to the cannon bone (metatarsus). Functionally, it’s the horse’s primary *propulsive joint*, converting muscular contraction from the gluteals and hamstrings into forward—and upward—motion. When you see a dressage horse collect or a racehorse drive from behind, you’re watching the equine hock anatomy in peak performance.

What forms the point of the hock in a horse?

The prominent “point” at the back of the hock is the **tuber calcis**—a robust, posterior extension of the **calcaneus bone** (the largest tarsal bone). It serves as the primary attachment site for the **common calcaneal tendon** (equivalent to the human Achilles tendon), which includes the gastrocnemius, superficial digital flexor, and biceps femoris muscles. A well-defined, firm point is *normal* and desirable; swelling, heat, or asymmetry here may indicate trauma (e.g., capped hock) or deeper joint issues. The equine hock anatomy relies on this bony landmark for leverage—and resilience.

What is the point of the hock?

Functionally, the **point of the hock** (the tuber calcis) acts as a *mechanical lever*—maximising the pull of the gastrocnemius and other extensor muscles to generate powerful propulsion. Without this bony prominence, the tendon would attach closer to the joint axis, drastically reducing mechanical advantage (like shortening a wrench). Evolutionarily, it’s a masterpiece of efficiency: a small bony projection that multiplies force, enabling horses to gallop, jump, and spin with explosive agility. In short, the equine hock anatomy’s “point” isn’t decorative—it’s *essential*. Lose it, and you lose thrust.

References

- https://www.rvc.ac.uk/research/equine-biomechanics-hock-propulsion-2023

- https://www.beva.org.uk/publications/hock-pathology-clinical-guidelines-2024

- https://www.hartpury.ac.uk/equine-science/joint-fusion-ontogeny-study

- https://www.farrierassociation.org.uk/technical/hoof-hock-biomechanical-link