Parts to a Horse Labeled Body Parts Guide

- 1.

What are the parts of a horse? Let’s start with the bits that don’t *neigh* back

- 2.

What are the 3 F's for horses? No, not “faff, fettle, and fizzy pop”—though that’s 70% accurate

- 3.

What are the distal limbs of a horse? The lower leg—where magic and mayhem collide

- 4.

What are the 4 quadrants of a horse? Not geography—just common sense with a chalk line

- 5.

The head: more than just a pretty face and a hay vacuum

- 6.

The back & barrel: where “sore back” isn’t just an excuse to skip mucking out

- 7.

The hindquarters: the engine room, where power’s brewed like strong Yorkshire tea

- 8.

The mane, tail & skin: aesthetics with *actual* function

- 9.

Common mislabels—because “knee” isn’t the knee, and “ankle” isn’t the ankle

- 10.

Where to go next? Because knowing the bits makes every ride deeper

Table of Contents

parts to a horse

What are the parts of a horse? Let’s start with the bits that don’t *neigh* back

Ever tried explaining a horse to someone who’s only seen them in *Peaky Blinders* and thinks they’re just “big dogs with hooves”? Bless their cotton socks. The parts to a horse aren’t just a list—they’re a symphony of form, function, and centuries of selective breeding. From poll to pastern, withers to whiskers—every inch’s got a name, a job, and usually a story. Think of it like reading a vintage Land Rover: bonnet, bulkhead, axle, diff—except this one *breathes*, *learns*, and occasionally kicks the stable door off its hinges. A proper parts to a horse chart? Not just for vets. It’s your passport to reading movement, spotting soreness, and nailing that perfect groom. And yes, even the *frog* has its moment—more on that later, you cheeky lot.

What are the 3 F's for horses? No, not “faff, fettle, and fizzy pop”—though that’s 70% accurate

Right-o—this one’s a yard classic. Ask any seasoned groom, and they’ll grin: “The Three F’s? Forage, Friends, and Freedom.” Simple? Profound. Forage = fibre-first diet (hay & grass, luv—not muesli bars and sugar cubes). Friends = herd mates. Isolation’s cruel—horses are hardwired for company, like tea needs a biscuit. Freedom = movement. Box rest’s for injury rehab, not lifestyle. Let ’em stretch, trot, roll, and *breathe*. Miss one F? Behavioural niggles creep in—wood-chewing, weaving, wind-sucking—like a kettle left whistling too long. And while it’s not *anatomical*, understanding the parts to a horse means seeing the whole being—not just the musculoskeletal bits, but the mind, gut, and social wiring too.

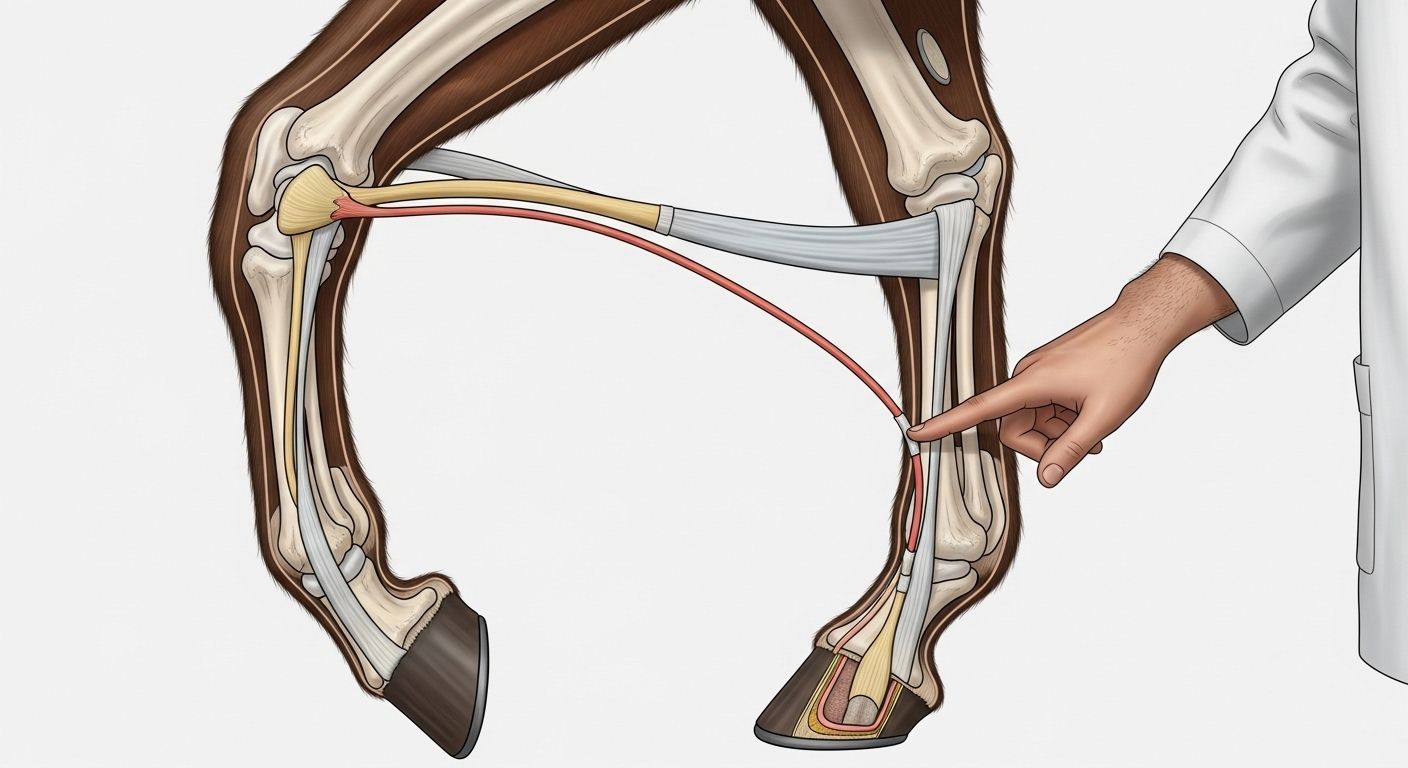

What are the distal limbs of a horse? The lower leg—where magic and mayhem collide

“Distal limb” sounds posh, like something off a BBC documentary narrated by David Attenborough in a tweed waistcoat. But in plain Mancunian: it’s *everything below the knee or hock*. And here’s the kicker—no muscles down there. Zip. Nada. Just bone, tendon, ligament, and keratin, working like a Swiss watch dipped in WD-40. Front: cannon → fetlock → pastern → coffin bone → hoof. Hind: same, but hock-to-hoof. It’s the distal limbs of a horse that take 70% of impact at trot, 90% at gallop. They’re elastic, spring-loaded, and *fragile* if mismanaged. A crisp parts to a horse diagram always spotlights this zone—labelled, cross-sectioned, often with force arrows pointing *everywhere*. Because down here? A millimetre off = months out.

What are the 4 quadrants of a horse? Not geography—just common sense with a chalk line

Vets and farriers love their grids. The 4 quadrants of a horse divide the hoof sole into—yes—four sections: *left front*, *right front*, *left hind*, *right hind*. Why? For precision. Thrush in LF? Lameness in RF? Sensitivity in LH? Pinpointing helps track progress (or decline). Some extend the quadrant system to the *whole body*—"cranial left", "caudal right"—but hoof-wise, it’s pure pragmatism. Think of it like a satnav grid-reference: “Pain at 7 o’clock in RH sole, near bar-heel junction.” Suddenly, you’re not guessing—you’re *diagnosing*. And any top-notch parts to a horse reference will include hoof quadrants, often shaded like a pie chart gone minimalist.

The head: more than just a pretty face and a hay vacuum

Let’s break down that noble noggin. Starting top: poll (just behind ears—where headstalls sit), forehead, muzzle (mobile, sensitive, covered in whiskers—*never clip those!*), nostrils (flaring = emotion or effort), eyes (side-placed for near-360° vision, but blind spots *right* in front and *directly* behind), and jaws (powerful, but teeth need floating every 6–12 months—£60–£120, depending on sedation). Oh, and the bars inside the mouth? Not pub snacks—they’re the toothless ridges guiding bit placement. A labelled parts to a horse head diagram looks like a Victorian anatomist’s doodle: elegant, obsessive, *spot on*.

The back & barrel: where “sore back” isn’t just an excuse to skip mucking out

That smooth curve from withers to croup? Built for burden—and balance. Withers (highest point, where saddle sits), back (thoracic vertebrae—longissimus dorsi runs the length), loin (between last rib and point of hip—weak here = “swayback”), barrel (ribcage—18 pairs, protecting lungs, heart, gut), and flank (soft dip behind ribs—watch it hollow if they’re colicking). Saddle fit? Critical. A 2cm pressure point = muscle atrophy in 3 weeks. And yes, “cold-backed” isn’t myth—it’s delayed muscle relaxation post-rest. A full parts to a horse schematic shows dorsal landmarks *and* underlying musculature—because you can’t understand movement without seeing what’s *under* the hair.

The hindquarters: the engine room, where power’s brewed like strong Yorkshire tea

This is where *go* happens. Croup (top line, slope affects gait), point of hip, point of buttock, stifle (our knee—prone to OCD in young horses), gaskin (thigh muscle—massive in jumpers), and hock (our ankle—complex, 11 bones!). The gluteals and hamstrings here generate propulsion—up to 90% of thrust in canter. Weak hindquarters? Short strides, reluctance to collect, “pea-shooter” behind. A dynamite parts to a horse illustration layers muscle over bone here—red fibres snaking around white struts—because power’s useless without structure to channel it.

The mane, tail & skin: aesthetics with *actual* function

Mane? Not just for plaits and YouTube glamour shots. It shields the neck from sun, rain, and biting flies—like a built-in umbrella. Tail? Swatter, signal, mood ring. A clamped tail = pain or fear; high-carried = alert or excited; swishing *without* flies? Often back pain. And the skin? Thickest on neck/chest (~5mm), thinnest on eyelids (~1mm). It’s the largest organ—sweat glands for cooling, sebaceous glands for waterproofing, nerve endings *everywhere*. Clip too close in winter? You’ve stripped natural insulation. Ignore rain rot? Hello, bacterial party. Even in a basic parts to a horse outline, these get labelled—not as “decor”, but as *defence*.

Common mislabels—because “knee” isn’t the knee, and “ankle” isn’t the ankle

Let’s clear the yard fog once and for all:

- “Knee” = actually the *carpus* (our wrist)

- “Ankle” = actually the *fetlock* (our knuckle)

- “Elbow” = the *true elbow*—back of front leg, below withers

- “Hock” = the *tarsus* (our ankle—yes, really)

- “Chestnuts” = not food—they’re vestigial toe pads (front: above knee; hind: inside hock)

Mix these up, and you’ll sound like a tourist asking for “the loo” in a chip shop. Precision matters—especially when describing lameness. “Left front fetlock heat” gets a vet moving faster than “left front ankle wobbly bit.” And every authoritative parts to a horse guide corrects these myths upfront—bold, italic, *underlined if needed*.

Where to go next? Because knowing the bits makes every ride deeper

Still hungry? Good. Start at the source: Riding London—our little corner of the equine internet, brewed strong and served with a side of common sense. Fancy structured learning? Dive into our Learn section—glossaries, videos, vet Q&As, the lot. And if you want the *full* lowdown on one of the most high-stakes zones, don’t miss our companion deep-dive: anatomy of a horse’s leg: bone and tendon map—with 3D layering, injury hotspots, and trimming biomechanics. Because knowing the parts to a horse isn’t just trivia—it’s respect. And respect? That’s the first stride toward partnership.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the parts of a horse?

The parts to a horse span external landmarks (poll, withers, cannon, fetlock, hoof) and internal structures (coffin bone, navicular, longissimus dorsi, stifle joint). Key zones: head (muzzle, eyes, ears), neck (crest, throatlatch), trunk (withers, back, barrel, loin, croup), limbs (shoulder, knee/carpus, cannon, fetlock, pastern, hoof), and hindquarters (stifle, gaskin, hock). A comprehensive parts to a horse reference includes both surface terms and underlying anatomy for functional understanding.

What are the 3 F's for horses?

The 3 F’s for horses are Forage (continuous access to fibre-rich roughage), Friends (social contact with other horses), and Freedom (opportunities for movement and natural behaviours). These are foundational to equine welfare—neglecting any one increases risks of colic, stereotypies, and laminitis. Though not anatomical, the 3 F’s contextualise the parts to a horse within holistic health, reminding us that structure serves function—and function thrives on environment.

What are the distal limbs of a horse?

The distal limbs of a horse refer to the segments *below* the carpus (front “knee”) or tarsus (hind “hock”), comprising the cannon bone, fetlock joint, pastern bones (P1 & P2), coffin bone (P3), navicular bone, flexor tendons (SDFT/DDFT), suspensory ligament, and hoof capsule. Critically, this region contains *no muscles*—movement relies on tendons acting over distance. Understanding the parts to a horse distal limb is essential for lameness diagnosis, trimming, and performance management.

What are the 4 quadrants of a horse?

The 4 quadrants of a horse typically refer to the division of *each hoof sole* into left front, right front, left hind, and right hind sections—used by farriers and vets for precise lesion mapping (e.g., “thrush in LF quadrant”). Some extend this to full-body assessment (cranial/caudal × left/right), but hoof quadrants are standard in trimming and pathology notes. Including quadrant awareness in a parts to a horse guide elevates it from basic labelling to clinical utility.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541074

- https://www.bevas.org.uk/uploads/documents/Equine%20Anatomy%20Reference%20Guide%202023.pdf

- https://www.merckvetmanual.com/musculoskeletal-system/anatomy-of-the-equine-musculoskeletal-system/overview-of-equine-anatomy