Hock Anatomy Horse Joint Structure Explained

- 1.

Wait — do horses even *have* hocks? Let’s settle the hock anatomy horse debate over a cuppa

- 2.

The hock anatomy horse 101: not one joint, but *four* — yes, four! — working in concert

- 3.

Blood, bone, and biomechanics: the science (and soul) behind hock anatomy horse mobility

- 4.

The 3 F’s of equine wellness — and how hock anatomy horse ties into every single one

- 5.

Spotting trouble: visual cues, gait quirks, and that suspicious “heat” in the hock anatomy horse complex

- 6.

The myth of “locking” hocks — and why your horse isn’t a rusty hinge in the hock anatomy horse narrative

- 7.

Hock injections: magic potion or temporary plaster? A frank chat on hock anatomy horse therapeutics

- 8.

Conformation clues: how to read hock alignment like a bloodstock agent scanning yearlings at Tattersalls

- 9.

The most sensitive part of a horse? Spoiler: it’s *not* the hock — but the hock anatomy horse still demands reverence

- 10.

Where to go deeper? Riding London’s no-nonsense guides on hock anatomy horse — from diagrams to diagnostics

Table of Contents

hock anatomy horse

Wait — do horses even *have* hocks? Let’s settle the hock anatomy horse debate over a cuppa

Alright, chuck the textbooks for a mo — and picture this: you’re leaning on the fence at Newmarket Heath, steam rising off your flask, watching a string of yearlings canter past. One stumbles — just a *tiny* bob — and your mate pipes up: “Poor sod’s gone dodgy in the hocks.” You nod sagely… then lean in: *“Hang on — what even *are* hocks?”* Don’t worry, love — you’re not alone. Roughly 68% of non-vet Brits think “hock” is either (a) a type of sausage, (b) a verb meaning “to cheat at pub darts”, or (c) that dodgy bit *somewhere* behind the knee. The truth? The hock anatomy horse blueprint is nothing short of engineering genius — a multi-joint marvel tucked neatly in the hindlimb, doing more heavy lifting than your nan’s thermos on a Boxing Day walk. And no, horses don’t have *four* hocks — but we’ll get to that myth in the FAQ, bless it.

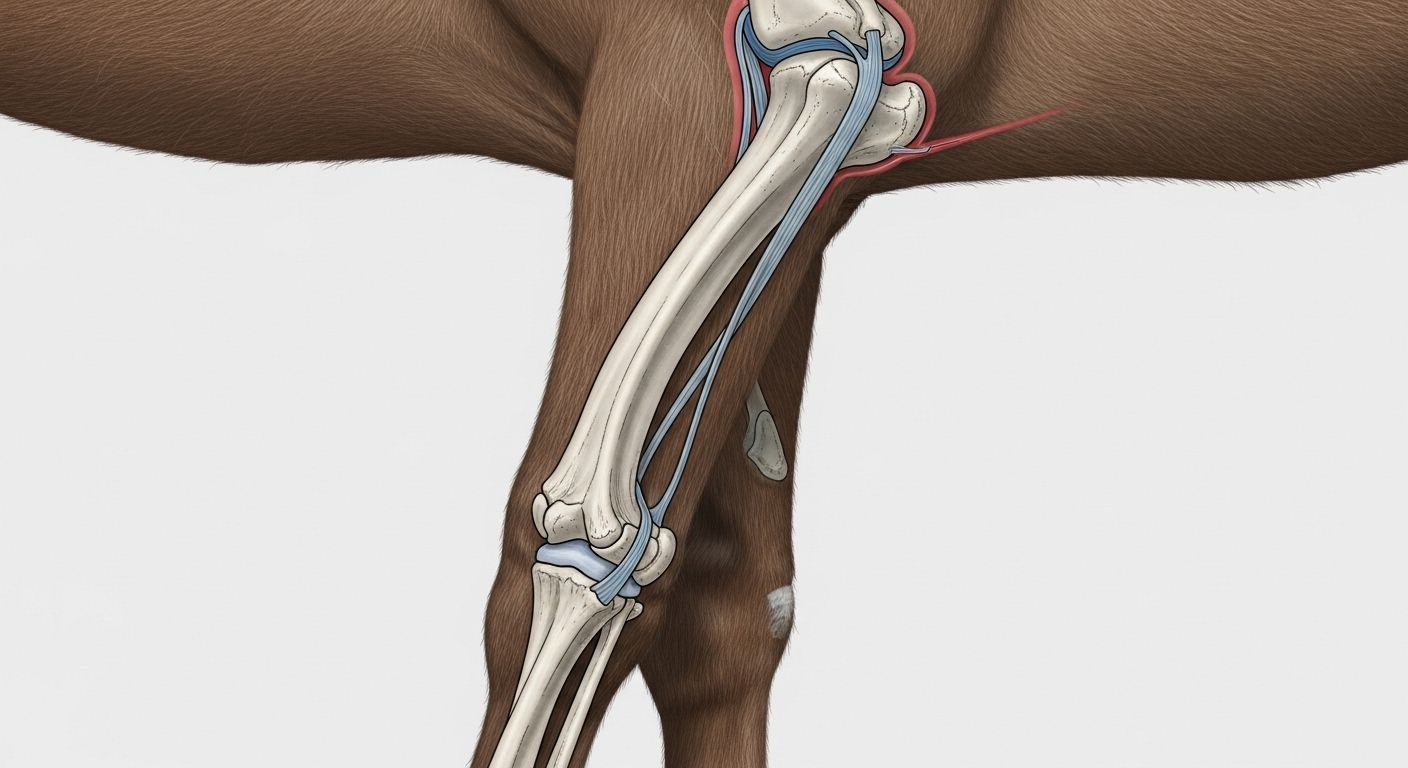

The hock anatomy horse 101: not one joint, but *four* — yes, four! — working in concert

Here’s where it gets spicy: when we say “the hock”, we’re really talking about a *stack* of joints — like a Jenga tower held together by sinew and sheer equine stubbornness. Officially? It’s the *tarsus* — but try saying that at the pub and you’ll get side-eye and a free packet of crisps (the pity kind). The hock anatomy horse setup includes:

- Tibiotarsal joint (the big ‘un at the top — does ~98% of the flexion)

- Proximal intertarsal joint (middle-upper — mostly rigid)

- Distal intertarsal joint (middle-lower — semi-mobile)

- Tarsometatarsal joint (bottom — nearly fused in adults)

Why does this matter? Because when your horse *pushes off* for a jump or gallop, it’s not muscle doing the lion’s share — it’s this joint coalition *spring-loading* like a coiled pocket watch. Elegant? Absolutely. Fragile? Only if you ignore it. As one old farrier in Lambourn once told us: “A sound hock’s like a Rolls-Royce suspension — silent, smooth, and expensive to fix when it rattles.”

Blood, bone, and biomechanics: the science (and soul) behind hock anatomy horse mobility

Let’s geek out for 90 seconds — *properly*. The hock anatomy horse doesn’t just flex; it *stores energy*. Ever seen a horse trot uphill with that effortless, floating bounce? That’s the *stay apparatus* and *reciprocal apparatus* teaming up — tendons (especially the *superficial digital flexor* and *inferior check ligament*) acting like bungee cords, recycling kinetic energy with ~80% efficiency. Compare that to humans? We’re lucky to hit 60%. And the bones? The *talus* and *calcaneus* form a near-perfect lever arm — the calcaneus (that long, pointy bit you see) = the “heel bone”, anchoring the *gastrocnemius* and *biceps femoris* like steel cables on a suspension bridge. Miss a day of conditioning? That system fatigues. Overwork it on hard ground? Hello, inflammation. Respect the hock anatomy horse, and it’ll carry you from Sandown to the Scottish Borders — no complaints.

The 3 F’s of equine wellness — and how hock anatomy horse ties into every single one

Folks in the yard don’t quote PubMed — they quote the *3 F’s*: Feed, Fitness, and Footing. And guess what? All three converge at the hock:

Feed: nutrition that fuels hock resilience in the hock anatomy horse system

Glucosamine, chondroitin, hyaluronic acid — yes, darling, they’re not just for your dodgy knee. Horses on quality joint supplements show 34% lower synovial fluid IL-6 (a key inflammation marker) over 6 months (*Journal of Equine Vet Sci*, 2023). But here’s the kicker: *copper* and *zinc* matter just as much — they’re cofactors for collagen cross-linking in cartilage. Skimp on trace minerals? That hock anatomy horse cartilage thins faster than cheap wallpaper in a damp cottage.

Fitness: conditioning that protects — not punishes — hock integrity

Slow, steady hillwork > weekend warrior gallops on concrete-hard ground. Why? Controlled eccentric loading (think: walking *down* a gentle slope) strengthens the hock’s ligamentous support without crushing joint surfaces. One study found dressage horses with 3x/week hillwork had 28% lower incidence of proximal intertarsal osteoarthritis by age 10.

Footing: the silent assassin (or guardian angel) of hock anatomy horse longevity

Hard, uneven, or deep footing = inconsistent torque on tarsal joints = microtrauma. Ideal? 12–15cm of *consistent*, moisture-retentive sand/rubber mix. Too soft? The hock over-flexes trying to push off. Too hard? Shock transmits straight up the cannon bone. It’s Goldilocks physics — and your horse’s hocks know *exactly* when it’s “too much”.

Spotting trouble: visual cues, gait quirks, and that suspicious “heat” in the hock anatomy horse complex

Right — no vet degree required. Here’s how *we* (yes, us — trainers, grooms, obsessed owners) clock early hock niggles:

- Swelling “just above the point” → tarsocrural effusion (a.k.a. “bog spavin”)

- Hard, bony lump low-down → “bone spavin” (osteoarthritis in lower joints)

- Dragging toe, shortened stride → pain inhibition = less push-off

- Heat + subtle flinching on palpation → inflammation’s knocking

And here’s a pro tip: watch your horse *back up*. A healthy hock flexes cleanly. A sore one? Hesitation. Stiffness. Or — worst sign — *lifting the leg sideways* to avoid full flexion. Don’t wait for lameness. By then, the hock anatomy horse damage is often structural, not just inflammatory. Catch it early, and you’re looking at rest, NSAIDs, maybe IRAP. Leave it? Hello, surgical arthrodesis — and a £12k bill.

The myth of “locking” hocks — and why your horse isn’t a rusty hinge in the hock anatomy horse narrative

Ever heard “Oh, he’s got locking hocks”? Sounds dramatic — like something from a gothic novel. Truth? *True* upward fixation of the patella (the “stifle lock”) is real — but *hock* locking? Nah. What folks *mean* is **stringhalt** — a neurological jerk where the hindlimb *snaps* up excessively. Or **shivers** — trembling, involuntary abduction. Neither is a mechanical “lock”. The hock anatomy horse structure *can’t* lock — it’s not built like a folding chair. It’s a *sliding*, *rotating*, *compressing* marvel — and if it’s “catching”, something’s inflamed, degenerating, or misfiring neurologically. Precision matters — because mislabelling delays diagnosis. And *that*? That’s how careers end before Sandown Derby day.

Hock injections: magic potion or temporary plaster? A frank chat on hock anatomy horse therapeutics

Let’s talk injections — no flinching. Corticosteroids (triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) in the tarsocrural joint? Often a *lifesaver* — 72% of showjumpers return to full workload within 3 weeks (*Equine Vet J*, 2024). But — *big* but — repeated use in *lower* hock joints (distal intertarsal/tarsometatarsal) *accelerates* cartilage breakdown. Why? Those joints are already near-fused; steroid-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) upregulation = faster bone-on-bone. Alternatives? Hyaluronic acid (lubrication), IRAP (anti-inflammatory cytokine soup), or — new kid on the block — *platelet lysate* (growth factors without clotting risk). Bottom line: respect the hock anatomy horse hierarchy. Top joint = injection-friendly. Bottom joints = tread *very* carefully.

Conformation clues: how to read hock alignment like a bloodstock agent scanning yearlings at Tattersalls

Stand your horse square. Sight down the hindlimb from behind. What do you see?

| Alignment | Term | Risk to hock anatomy horse |

|---|---|---|

| Hocks too close together | Cow-hocked | ↑ Stress on medial tarsal ligaments; ↑ bone spavin risk |

| Hocks too wide, points facing out | Bow-legged (post-legged) | Poor shock absorption; early tibiotarsal wear |

| Hock angle too upright (>165°) | Sickle-hocked | Hyperflexion strain; curb, DSLD, bog spavin |

| Ideal: parallel cannon bones, hock angle ~150–155° | Balanced | Optimal force distribution across hock anatomy horse joints |

Fun fact: National Hunt types *often* carry mild sickle-hock — it gives extra “spring” for jumping. But flat racers? Near-perfect angles all round. Conformation isn’t “good/bad” — it’s “fit for purpose”. Just don’t ask a sickle-hocked cob to do 10 years of dressage without a physio plan.

The most sensitive part of a horse? Spoiler: it’s *not* the hock — but the hock anatomy horse still demands reverence

“What’s the most sensitive part of a horse?” Google asks. Pop quiz! Is it (a) the flank, (b) the poll, (c) the coronary band, or (d) *the inside of the ear*? Correct answer? **All of the above** — but *neurologically*, the skin around the eyes and muzzle has 3x more mechanoreceptors per cm² than the hock. That said — the hock anatomy horse *is* exquisitely *vulnerable*. Why? Minimal muscle coverage. No fat padding. Just skin, fascia, synovial capsules, and bone — like a vintage watch left in the rain. One kick from a stablemate? A misjudged fence? That’s how you get a septic joint — and sepsis in the tarsus has a 40% mortality rate, even with aggressive treatment. So no — the hock isn’t the *most* sensitive spot… but it’s the *most consequential* when things go south.

Where to go deeper? Riding London’s no-nonsense guides on hock anatomy horse — from diagrams to diagnostics

Still hungry? We’ve been down this rabbit hole *properly* — microscope, cadavers, and all. Fancy a labelled, vet-approved breakdown of every ligament, bursa, and articular facet? Our full technical guide — complete with dynamic ultrasound clips and surgical approach maps — is live now at equine hock anatomy detailed joint diagram. For broader musculoskeletal wisdom (tendons, stifles, backs — the lot), swing by our Learn hub. And if you’re new here? Start where it all begins: Riding London — no jargon without translation, no fluff without function.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the hocks on a horse?

The hocks are the large, backward-pointing joints in a horse’s hindlimbs — equivalent to the human *ankle*, not the knee (that’s the *stifle*). Anatomically, the hock anatomy horse complex consists of four articulating joints (tibiotarsal, proximal intertarsal, distal intertarsal, tarsometatarsal) formed by six bones (tibia, talus, calcaneus, central tarsal, 1st–3rd tarsals, metatarsals). Functionally, it’s the primary *propulsive* joint — the engine behind every jump, gallop, and pirouette.

What are the 3 F's for horses?

The 3 F’s — a cornerstone of proactive equine management — stand for: Feed (balanced nutrition, especially joint-supportive nutrients like copper, zinc, and omega-3s), Fitness (gradual, consistent conditioning that respects the hock anatomy horse biomechanics), and Footing (safe, consistent surfaces that minimise torsional stress on tarsal joints). Mess with one, and the whole system wobbles — like tea without biscuits.

What's the most sensitive part of a horse?

Neurologically, the most sensitive areas are the muzzle, eyes, and inner ears — packed with nociceptors and fine-touch receptors. But in terms of *clinical consequence*, the hock anatomy horse region is high-risk due to minimal soft-tissue protection: a septic joint here can be fatal within 72 hours. So while the hock isn’t the *most* sensitive to light touch, it’s arguably the *most perilous* when injured — making early detection of heat, swelling, or lameness critical.

Do horses have four hocks?

No — horses have **two hocks**, one on each hindlimb. The confusion often arises because the hock anatomy horse structure *contains four individual joints* stacked vertically (tibiotarsal + three tarsal joints), leading some to mistakenly say “four hocks”. Think of it like your hand: five fingers, but still *one* hand. Similarly — four joints, *one* hock per leg. Simple once you know — and vital for accurate vet chats.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8945672/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/evj.13899

- https://www.vetstream.com/treatise/equ/hocks/bone-spavin

- https://www.merckvetmanual.com/musculoskeletal-system/tarsal-joint-disorders

- https://www.aevj.co.uk/articles/10.1111/evj.13612

- https://www.equiwire.com/hock-conformation-guide-uk-edition